Guest Research Contributions

Italian-Scots to Scottish-Italians

‘Tallys’, Cafés and Chippies - Their Story and Mine!

by Raffaello Gonnella

History and Background, 1880 - 1910

Italians immigrants first came to Britain in the very late 19th Century, settling firstly in London. By the start of the 20th Century these same Italians had been joined by others and had spread out to most of the major cities in the U.K.

Why were these Italians leaving their homes and families in their native Italy? The relatively new country of Italy was formed officially in 1861 but by the 1880s many Italians found themselves living below the poverty line. New horizons looked to be the best prospect of bettering themselves. The mass emigration of Italians to the United States of America has been quite well documented and scenes of shiploads of emigrants sailing past the statue of Liberty to land at the immigration centre on Ellis Island have been popular scenes in many films! But many other Italians did not make it as far as the U.S.A. Those Italians coming to Britain spread out, heading for Liverpool and Glasgow, and having got that far many decided not to go any further. Liverpool, being a major employer and important dock and port. While Glasgow was ‘The Second City of The British Empire’, enjoying a golden period in its history.

Scottish Italians, 1910 – 1939

There are no accurate statistics but there are undoubtedly thousands of contemporary Scots who can trace their Italian origins back to Northern Tuscany and the small Tuscan village of Barga and the surrounding countryside area of Garfagnana or to the southern area of Picinisco, and the Frosinone region including Cassino, Atina and Val di Comino. These immigrants were a uniformly and independent minded lot, and very few of the incomers had any intention of working for any other employer. Their ambition was to be their own masters. Their employment in the early days was varied, but the bulk drifted towards what is grandly known as the ‘catering service’.

The modest café was commonplace in Italy but an innovation to Scotland, for which the Italians were largely responsible. In its own small way, its introduction was a revolutionary departure and one which added colour to the life of the nation, since it provided working class men and more especially women with a social meeting place. Some people regarded this novelty with dread and suspicion and Scotland, being what it is, there were those who were convinced that the café could only bode ill for the moral welfare of the people. And, of course, no district in any city town or village did not boast an Italian café or a fish and chip shop, always fondly referred to as ‘the chippie’, and proprietors of both catering establishments as ‘The Tallys’.

The desire to remain independent, allied with the choice of employment, meant there was never a ‘little Italy’ in Glasgow or any of the other UK towns or cities – the Italians spread themselves out. Because no matter how prosperous the districts in the city were, each district could only support two or three catering establishments. And these new Italian–Scots moved to where the work was to be found, immersing themselves into the host culture juggling the introduction of their new home and country with their memory and love of the land of their birth.

During the First World War, 1914-1918, Italy was an ally of Britain. Some Italians who had made new lives for themselves in Britain did feel compelled to return home and join the Italian Army. After 1918, the early immigrants who had arrived before 1914 had begun to prosper and word was sent back to towns, villages, hamlets and family in Italy for others to join them in this new adventure. For the next 20 years everything moved forward – every neighbourhood accepted their new Italian neighbours; the children of these immigrants made friends and went to school, most were bi-lingual, speaking Italian at home, and English both at school and when out playing with their Scottish friends. But the mothers and fathers still clung to their Italianism and families tended to spend leisure times with other Italian families, speaking their own language freely and catching up on news from ‘home’.

Sunday was a day off, when the shop was closed, and these days were always spent with family. A full sit-down meal with the family all together was standard; later other people would go to each other houses for a visit, the men and women separating, the men to play cards and have a few tumblers of vino and the women all busy talking together. Italian Clubs were also set-up in some of the bigger locations. In Glasgow there was the famous Casa D’Italia in Park Circus. Special occasions and celebrations took place, but it was mostly dances, organised in the hope that Italian boys and girls would meet and eventually marry. The dream of joining two Italian families together was high on their hopes.

The War and Internment, 1940 – 1945

By the middle of the 1930s events and the political situation in Europe and beyond began to change quite dramatically and quickly. By 1939, Britain and France were at war with Germany. After the Munich crisis of 1938 war was unavoidable. Among the precautions the British Government took was the passing into law, only two weeks before the outbreak of war, the Emergency Powers Act (1939), clause 18B of which dealt with the possible threat from British nationals. Foreigners could simply be detained under the Royal Prerogative, which required no legislation and guaranteed no appeal; in effect a suspension of Habeas Corpus, effectively ascribed them to one of three categories:

A: High Risk. Majority interned immediately.

B: Doubtful. Allowed to remain at liberty subject to travel restrictions.

C: No Risk. Allowed to carry on as normal.

In 1940 the situation escalated again when, on 10th June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain and her allies, and joined the war on the side of Germany. Churchill, the British Prime Minister, reacted to Italy’s declaration of war and the question of what was to become of Italians in Britain by issuing his infamous decree to “Collar the lot”. An order to arrest all Italian males aged between 16 and 70 was issued. Literally overnight, everything changed for Italians and their families living and working in Britain! Mobs went on the rampage and their targets were the shops of Italian owners, those same chippies and cafes that, only a few days before, they had frequented and enjoyed. The mobs smashed and looted, and in some extreme cases shops were set ablaze. Many Italians were injured trying to protect themselves their business and their families. Homes were visited and Italian males arrested; there was no set format or rules or order to these arrests. But it appears that membership lists of Italian clubs were obtained and used as a basis for arrest. And obviously, it was easier with the resources available to arrest and imprison Italian males from the main cities and towns. It took a lot longer to get the word and instructions out to the smaller towns and villages scattered across Scotland. By the end of June 1940, the response to Churchill's `collar the lot' was put into top gear; Home Secretary Sir John Anderson ordered the round-up of the harmless, the category C aliens, and another 13,000 Italians swelled the numbers in the makeshift camps to nearer 30,000. George Orwell observed that he could not get a decent meal in London as the chefs from the Savoy, the Café Royal, the Piccadilly and most of Little Italy, had all been locked up. One camp was rumoured to hold no less than fourteen top London chefs.

The internment camps were under military control, haphazard, makeshift, unplanned, inconsiderate, insensitive, callous, criminal ... and it is from this period that most of the complaints about internment stem. The two most resounding complaints were the breaking up of families and the total deprivation of news, no newspapers, no radio and a cumbersome censorship of mail that led to a summer backlog of over 100,000 letters. Next was the loss of personal possessions, in particular the loss of documents such as passports and undeniably, there were plain acts of theft. The detention of German POWs alongside legitimate refugees was a cause of concern. A letter to the London Times on July 23rd protested about ‘scenes of persecution which have already been alleged’.

What to do with these thousands of men they had arrested and held in local police stations and jails? The powers-that-be commandeered accommodation such as barracks and schools and the internees were transported to holding camps such as Woodhouselea (near Edinburgh), Kempton Park and Lingfield racecourses, or direct to camps across the British Isles and away from the south coast. None had been designed for this purpose. In Bury, Lancashire, a derelict cotton mill had simply been wrapped in barbed wire. In Huyton, Liverpool an unfinished housing estate was commandeered. Of the many camps, the worst seems to have been the camp at Bury, known as Warth Mills. It was termed a temporary transit camp, but the conditions were scandalous, and temporary transit could mean at least a week's stay. Two thousand men were housed in this semi-derelict building. There were eighteen water taps and one bathtub; beds were only boards; there were neither tables nor benches; blankets were full of vermin, and they had to eat standing up. The lighting for the entire place came through the glass roof; partly broken, it also allowed the rain to come in. The commandant refused to give any drugs for the sick without payment. The officers confiscated wallets and the soldiers’ seized all suitcases and took anything they fancied.

The next question was of course what to do with the internees: The increase in numbers of those interned led to a serious space problem within the UK and the answer was to ship them to the colonies. A decision was taken at the War Cabinet to export these internees/aliens to Canada and Australia. The first group of 7,500 were selected and, in mid-June, the British Government approached the governments of both Australia and Canada, who both agreed to take 7,000 internees.

On June 24, 1940, the first ship, the SS Duchess of York, headed off to North America with 2,602 internees, mostly German prisoners of war; this was twice her normal capacity for passengers. She sailed from Liverpool and arrived in Quebec on June 28. The internees then travelled by train for over two days to Nipogen, Ontario, where a discarded mining camp had been converted to an internment camp. The SS Duchess of York was an ocean liner (20,021 tons) built by John Brown & Co, Clydebank (Yard No.524), for the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. Launched on the 28th September 1928, and completed in March 1929, she served on the Liverpool to St. John, New Brunswick route, via Belfast and Greenock. In 1940, she was requisitioned by the Admiralty as a troop ship. The Duchess of York’s mission to deport such a large group of men was seen as a great success.

On the 1st July 1940, the SS Arandora Star was loaded with over 800 Italians. Germans and Austrians arrived at Liverpool docks and they too were put on board. No one knew where they were going, nor were they told when they asked. The Arandora Star slipped anchor at Liverpool docks on Monday, 1st July 1940, bound for Canada. She slowly made her way past the Point of Ayre, then the Isle of Man, where later many others were to be interred.

Sailing at 15 knots, the Mull of Kintyre was soon in the distance and at about 3am on the 2nd of July 1940, the Arandora Star passed Malin Head, heading towards Bloody Foreland and out into the Atlantic. However, the Arandora Star met its fate when she was torpedoed by a German U-boat, submarine, U-47, 75 miles west of Bloody Foreland, Ireland at approximately 7am on the morning of 2nd July 1940. Almost 1700 were onboard the Arandora Star, crew, guards, Italians, Germans and Austrians.

Of the 734 Italians on board - 446 died

Of the 479 Germans/Austrians on board - 175 died

Number of crew and guards who died - 184

Total number of dead - 805

The Arandora Star was built at the Cammell Laird Shipyard, Birkenhead on Merseyside Liverpool, for the Blue Star Line Company. She was 535 feet long 15,300 tonnes and was launched on January 1927. In 1929, just two years after her launch, the Arandora Star underwent a major overhaul when she was converted into a luxury cruise liner by Fairfield of Govan, in Glasgow, to carry 164 passengers . The new, sleek looking 15,000-ton cruise liner was captained by Edgar Wallace Moulton. Captain Moulton was to take the Arandora Star on cruises to the most exotic ports and countries of the world. During the 1930s he took the Arandora Star on winter cruises to Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Trinidad, Florida, Cuba and the Canary Islands. The springtime saw her cruising in the Mediterranean, and in summer it was to Germany, Scandinavia and the Fiords of Norway. She became one of the world’s best-known cruise ships, and many of the world's top businessmen and women, royalty and literary figures, dined at the captain’s table.

The third ship, SS ETTRICK, departed on July 3 with 3,062 internees. The Ettrick was accompanied by a destroyer escort and safely reached its destination after a 10-day voyage. The internees were badly treated and sailed in overcrowded and filthy conditions. When the ship eventually docked at Quebec, the prisoners were kept on board for a further 12 hours without food and when they were eventually brought ashore, they were made to hang around on the dockside for another six hours. It was during this wait that all of their possessions were taken from them. They were eventually interned in an old disused fort, known as Camp 43, on the Isle Sainte Helene in Montreal.

The fourth ship, the Sobieski, followed on July 7 with 1,828 internees who ultimately made their way to a camp near Fredericton in New Brunswick. MS Sobieski was a Polish owned ship built by Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson, Wallsend. Launched on 25th August 1938 and completed on the 15th June 1939, she was almost immediately commandeered as a troopship. 11,030 tonnes, 155.8 metres in length with a beam of 20.4 metres and draft of 8.3 metres, she was powered by engines made by J. G. Kincaid & Co., Greenock.

The next shipments of internees planned were to go to Australia. The first, and as it turned out the only ship to depart, was HMT Dunera ,on July 10th, 1940. First of those who were on the Dunera were over 400 survivors of the Arandora Star, who had been disembarked at Greenock in Scotland from the Canadian destroyer St Laurent. Next were the 500+ German and Italian prisoners of war. And of the other 1500 men who went; many volunteered to go, deceived by false promises by camp commanders and others. The promises included, with some minimal restrictions, that enemy aliens would enjoy considerable personal freedom overseas and would be allowed to work at their chosen occupation.

The Isle of Man became the largest host to the interned’ men, women and even children were imprisoned there. The Isle of Man was a blessing to the security forces because of its geographical location. It lay squarely in the Irish Sea between Scotland, Ireland and England; a five-hour sailing from Liverpool, it was more isolated than any Hebridean island, governed by its own parliament and practically immune, either from attack or rescue. Camps sprang up in Onchan, Peel, Ramsey, Port Erin and Port St Mary. In Douglas, whole streets of seaside boarding houses had been cordoned off, the windows blacked out and the summer guests replaced with prisoners.

The Isle of Man, having its own parliament, also had its own rations standard, somewhat more relaxed than on the mainland, and there was always the possibility of trade with the locals. By the end of 1940, 10,000 interned aliens who had been held on the Isle of Man, and a few others from camps in mainland Britain, had begun to be released. Many were eventually released back to their civilian lives, some joined the forces; many were allowed to join the Pioneer Corps, a non-combatant regiment that laid roads and dug drains. They were often regarded as the army's dumping regiment, but undeniably useful.

War is Over, 1945 - 1949

After the war, wounds between Italians who had lived through the most traumatic time were still very raw. Many were still registered as enemy aliens and the uncertainty and lack of contact and information from their homeland added to the sense of anxiety. Men were released from internment, returning home to find businesses either no longer there or in a very poor state. The women had been left to manage as best they could, with the main concern being the children and their day to day safety. The businesses were just another problem to contend with and lack of support, low rations, and the general mayhem that war brings, meant many businesses simply folded or were at their lowest point. All those who did return to their families and were reunited, were the happy stories, but for many other families who lost a loved one, this meant a new time of worry, fear and uncertainty. But these Italians were a resilient lot and gradually life and businesses were re-built. Contact made with family in Italy only confirmed that their homeland was in even greater disarray than what it had been 20+ years previous, when it had first forced them to consider leaving. The loss of so many males was felt by all peoples and slowly the same café’s and chip shops began to appear flourish again.

1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

The late 1950s and the 1960s were the real zenith for chippies and cafes. The films of the time and news reports portrayed the USA-style drugstores and coffee shops, and then there was the rock‘n’roll era. Music and youth culture exploded, and teddy boys were followed by rock and rollers, and then mods and rockers. The start of the swinging 60s saw a massive upsurge in café popularity. These cafes introduced jukeboxes, neon lighting and American diner furnishings and fixtures, although some of the smaller cafes still retained the look and feel of a quaint sweetie shop. But for all of them, the products they sold were at the root of their popularity. Cones and nougats, sponges, oysters, wafers and 99s some dripping with raspberry sauce, known as ‘Tallys Blood’, went together with new cappuccino-spluttering coffee machines, serving the milky coffee in Pyrex cups and saucers and the glitzy neon-lit jukeboxes. Businesses flourished, life got better, and Italians enjoyed a new-found affluence and a level of total acceptance and integration.

Yet, they were still referred to as ‘Tallys’, and the school kids with the strange and funny sounding names were still teased about being ‘oily’ and ‘greasy’, and coming from homes that emitted strange smells and where freshly ground coffee, parmesan cheese and Salsiccia (Italian sausage) were hung up like a large deformed necklace. Family was still paramount and important but now mixed marriages (Italian to non-Italian) were much more common than same nationality marriages, and names were changed or anglicized to immerse these new Scots into their surroundings; and not just the children, the old thought it better also; old Giuseppe became Joe, Luigi became Ian, and Giovanni, John. The children born after the war years spoke only English. And anyway, any prejudices, jokes or jibes against these Italians and their families were fading away as there was now a new arrival to contend with, as a huge surge and sudden and quick influx of all the new immigrants arrived from the Indian sub-continent (India and Pakistan).

St Andrew's Cathedral’s Italian Garden

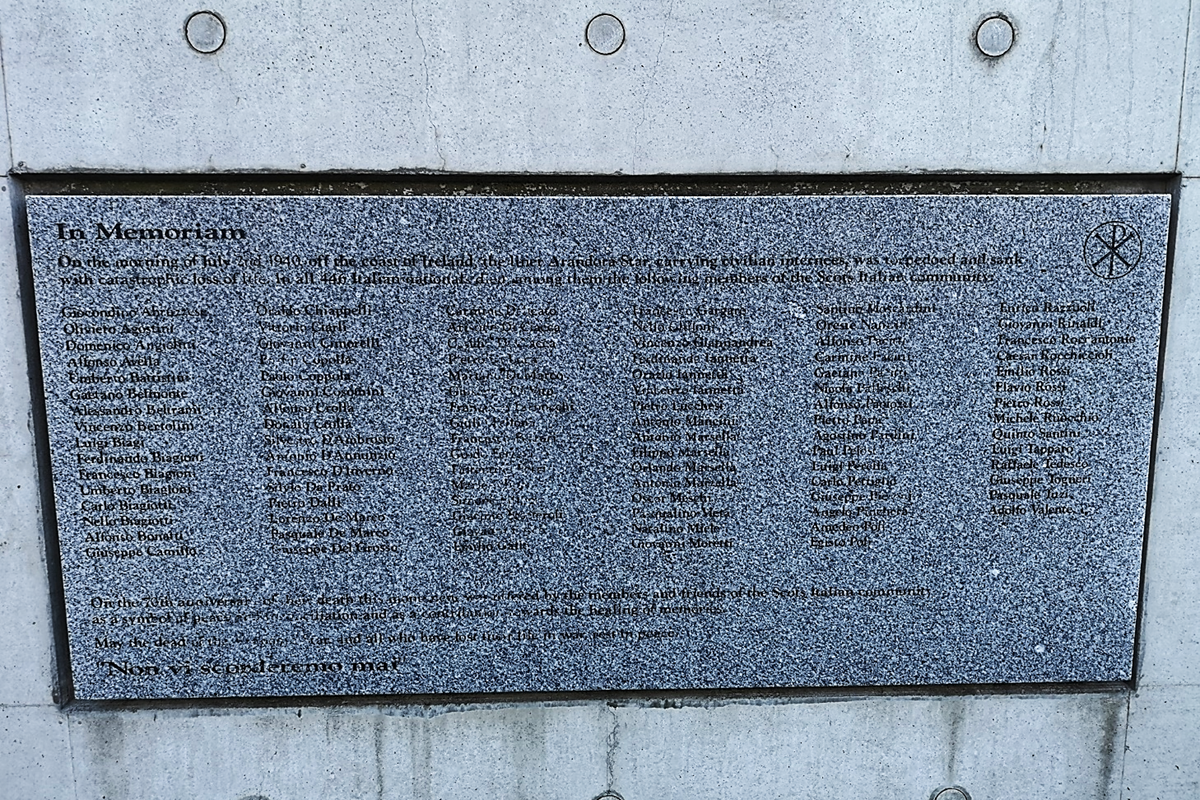

Today, families and descendants of those first Italian immigrant settlers have a monument and a reminder to everyone of what Italians brought to and gave to Scotland and the U.K. St Andrew's Cathedral’s Italian Garden was officially opened on Monday 16th May 2011. Following 18 months of work (which is still ongoing), a new and dramatic space has been created next to the Cathedral.

The garden has, as its focal point, a monument commemorating the Arandora Star tragedy. Designed by Roman architect Giulia Chiarini, its monumental mirrored plinths with inscriptions from the Gospel and Italian poets, is set in a grass and slate landscape. A 200-year-old olive tree, gifted by the people of Tuscany as a sign of peace and reconciliation, has been planted and a fountain and stream traverse the central space. Around the walls, marble plaques tell the story of the Cathedral, of the Catholic revival in Scotland, and of the Arandora Star tragedy. The names of every one of the Italian-Scots who drowned on the ship are carved on the central wall plaque. This splendid new facility is open from dawn to dusk and is fast becoming a favourite tourist spot for visitors in Glasgow. It offers a ‘breathing space’, a gathering area, and in future, maybe an exhibition area, a café space and a shop. It also provides a focus for a forgotten tragedy, which has never been appropriately marked - the new garden is the world's largest permanent memorial to all the victims of the Arandora Star, which on the morning of 2nd July 1940, off the coast of Ireland, was torpedoed and sank. In the sinking, 805 men perished, British, Germans and Italians. Of that total, 446 were Italian civilians, and of them, 96 were from Scotland.

There are other memorials to the victims of the Arandora Star in Scotland, England Wales and Italy. With the creation of the Italian Garden and the memorial to all who died aboard the Arandora Star, and with the wall plaque displaying all the names of those Italian-Scots who died, It now seems, thankfully, that the new Scottish-Italians will never let the tragedy be forgotten and as new modern Europeans they have their monument to mark their ancestors journey and their own history!

Evelyn Waugh and Patterton Camp?

by Rachel Kelly

On a more whimsical note, there has been some suggestion that the first army camp described in the prologue of the novel Brideshead Revisited, by Evelyn Waugh, is based, at least partly, on the WWII army camp at Patterton.

Waugh’s biographer, M G Brennan, places Waugh at a ‘Pollock Camp’. This may have been another army camp in the area. However, it is entirely possible that Waugh visited Patterton during his stay. It must be remembered that Brideshead Revisited is a work of fiction and that, therefore, the descriptions of the camp and the surrounding area might not be accurate and may be based on aspects of various camps that Waugh visited during the war. Brennan writes, ‘The prologue begins in 1942 with ‘C’ company and Ryder (like Evelyn, aged thirty-nine) about to leave the desolate Pollock Camp near Glasgow (recalling Evelyn’s dismal time there) for Brideshead.’ A lot of these camps would have been in a rural setting, but Waugh’s character Ryder’s description of the camp seems to hint at it being based, at least partly, on Patterton:

Here the tram lines ended, so that men returning fuddled from Glasgow could dose in their seats until roused by the conductress at their journey’s end… Here the close, homogenous territory of housing estates and cinemas ended, and the hinterland began.

Several respondents have stated that the Rouken Glen tram stopped at the end of the line, which was near to Patterton Camp. The sudden change from suburbia to countryside does seem to closely resemble the area during this era. It is also noteworthy that Waugh writes that the tram was returning from Glasgow. The camp was just on the border of Glasgow and Renfrewshire. Waugh states:

The camp stood where, until quite lately, had been pasture and ploughland; the farmhouse still stood in the fold of the hill and had served us for battalion offices; Ivy still supported part of what once had been the walls of a fruit garden; half an acre of mutilated old trees behind the wash-houses survived of an orchard. The place had been marked for destruction before the army came to it. Had there been another year of peace, there would have been no farmhouse, no wall, no apple trees. Already half a mile of concrete road lay between bare clay banks, and on either side a chequer of open ditches showed where the municipal contractors had designed a system of drainage. Another year of peace would have made the place part of the neighbouring suburb. Now the huts where we had wintered waited their turn for destruction.

This paragraph is full of clues that this could be partly a depiction of Patterton camp. The farmhouse in the fold of the hill. The Patterton farmhouse was on a hill above the camp. Here our respondent Jessie Jolliff, granddaughter of the Lambie family, who owned the farm from at least the 19th century up until 1952, describes the setting of the farmhouse:

It’s just beside the Patterton roundabout. You just go along that…you can’t actually get up to it now. But it just, it overlooks Glasgow and the view is totally… They were up at the back. The camp would be down in the hollow. Heading towards Spearsbridge. It would be a wee, sort ah, distance from it…It wasn’t just on the site that they lived…it was quite a bit down.

It is mentioned in the paragraph that the farmhouse served as battalion offices. This seems to suggest that the farmhouse was empty at the time, which it was not. It could be that this is a complete fiction. It is interesting, perhaps, that Jessie Jolliff also states that, it was related to her that her grandparents, who owned the farm at this point, provided accommodation for the wives of guards from the camp, during WWII:

My gran used to open up one of her rooms for, I think it was, the guards’ family to come and visit. I don’t know how often that would take place. I think they all basically just tried to work together. I think it was like, say their wives, came to visit the guards and things… you know, they were sort of in the camp and, sort of, couldn’t get away. I don’t know if they were kept in the camp. At first, I thought it was prisoners but that wouldn’t have been feasible. Em, but that was something…another way of her making some more money, you know… Like something that they did during the war to keep things sorta ticking over.

Waugh’s ‘The neighbouring suburb’ could be a reference to the Jenny Lind housing estate, which is close to the camp; it was built in the late 1930s and was a council estate. To this day, there are apples trees and fruit bushes in part of the area where the camp was. These may have been planted later, perhaps when the POWs were in the camp. The Italians who were there from 1944 to 1945 certainly had a garden. Gardening enthusiasts have suggested that the apple tree, in an area of woodland between the housing estate and the Patterton Railway Station just off Stewarton Road, looks around 70 years old.

Waugh mentions something called the ‘Pollock Diggings’ in his prologue. It is unclear to as to what this might refer but it does seem to be his name for what is described in the paragraph immediately preceding the use of the term:

The smoke from the cook houses drifted away in the mist and the camp lay revealed as a planless maze of short-cuts superimposed on the unfinished housing scheme, as though disinterred at a much later date by a party of archaeologists.

Of course, possible links between Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and Patterton Camp are, at this point, simply conjecture, but it is certainly an interesting idea…

.

Next Page: Contact Us