Patterton: The Military Presence

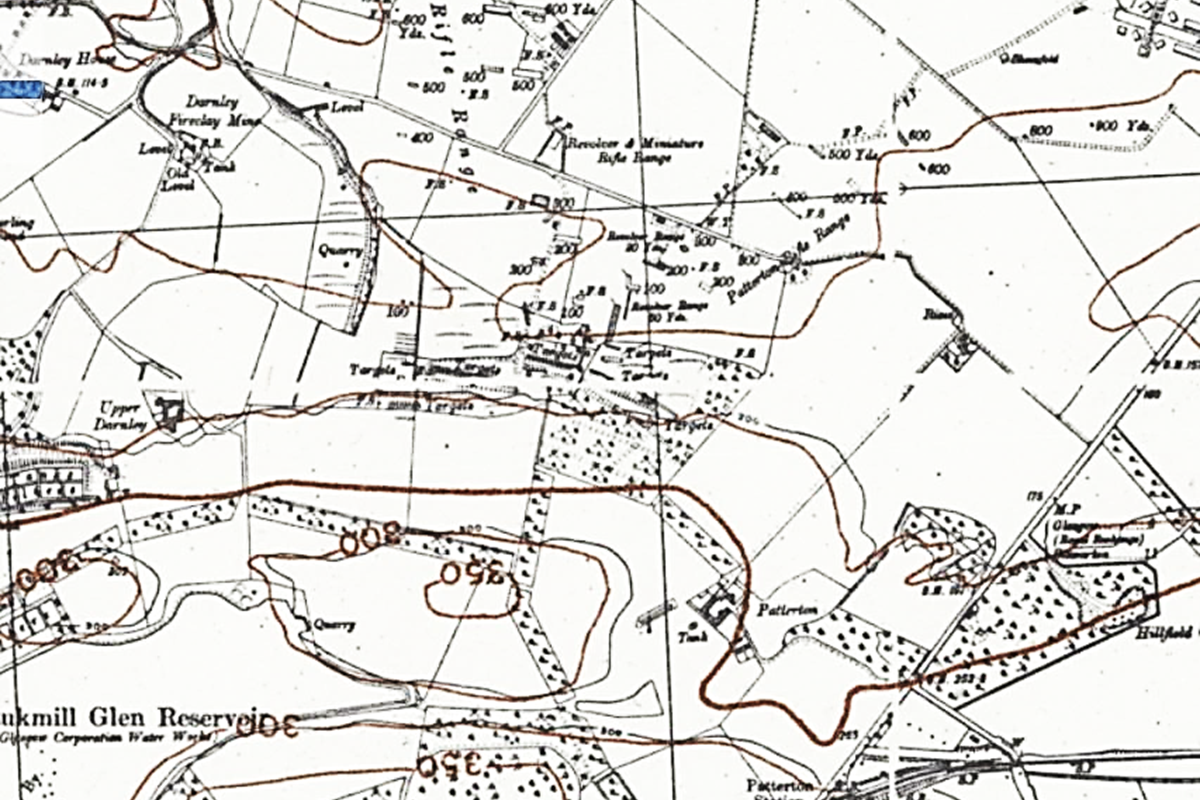

Prior to the outbreak of WWII, Patterton was a largely rural area near Thornliebank, Scotland; its few dwellings mainly facilitated farming, small-scale quarrying and transport activities. The area close to what later became Patterton Prisoner of War (POW) Camp housed two neighbouring rifle ranges. These were the Patterton Rifle Range and the Darnley Rifle Range, which were opened in the 1870s and the 1880s respectively. They first appear on the 1896-1899 ordinance survey (OS) map (second edition, first revision) and seem to have been most active on the OS map third edition (1914-1920), when army and territorial forces were preparing for WWI, the ‘Irish question’, and the following period of post-war industrial and social unrest. The rent books of the Nether Pollok Estate show that the rifle ranges were being rented by the Territorial Force from 1909 to 1922. There are no rent entries for the ranges after that, which suggests, as aerial photographs indicate, that the ranges fell out of use for a time. The ranges look to have fallen out of or perhaps diminished in use by the OS map 4th edition (1934-1938). However, our respondent, James Rodger (c.90 years of age), thinks that they were being used in the late 1930s for rifle practice, at the time when Britain was again preparing for war:

"I think they came up fae the Cooglen, for tae practice on the rifle range at Patterton. As far as I can recollect, pre-war, in the thirties."

What we know for certain is that Britain’s rifles ranges, such as those at Patterton and Darnley, were created to support the movement for volunteer soldiering, which resulted in the formation of the Volunteer Corps and the National Rifle Association in 1859. This all came about as a result of a few factors. Newspaper reporting of uprisings in India, in 1857 and 1858, revealed to middle class readers that women and children were not safe during some conflicts. There was also the, mostly unfounded, fear of French invasion after an assassination attempt on Napoleon III in 1858, which was carried out with the use of a bomb manufactured in Birmingham.

At that time, the British Army was mostly recruited from the ranks of the working- and upper classes and was frequently deployed abroad; in its absence, the middle classes began to feel that there was an imperative on them to help protect British shores. All over the country, the middle classes joined volunteer corps and, in effect, became a citizen army of part-time rifle, artillery and engineer corps. In the main, they took their roles seriously and often held competitions at their home rifle ranges and some would also compete nationally.

The craze continued long after fears of invasion had abated. This was partly due to a romance growing up around the Volunteer Force, encouraged, no doubt, by Alfred Tennyson, who captured the spirit of the time by publishing his poem ‘Riflemen Form’ in The Times on 9 May 1859. It was also a good way to find a wife and to generally impress the ladies, with the caveat that they were, at the same time, often lampooned in the press. As a basis for the units, many communities had rifle clubs for the enjoyment of the sport of shooting, and a whole industry of accessories, including beard oils and guns, grew up around the movement, thereby making being a member of a volunteer corps a fashionable pursuit. Other appeals which sustained the movement were that men who joined the volunteer corps were permitted to carry guns and could spend periods of time camping at the rifle ranges, thus offering some escape from the strictures of middle-class life.

Although originally highly autonomous, the units of volunteers became increasingly integrated with the British Army after the Childers Reforms in 1881, which reorganised the infantry regiments of the British Army, before forming part of the Territorial Force in 1908. Indeed, most of the regiments of the Territorial Army Infantry, Artillery, Engineers and Signals units are directly descended from Volunteer Force units.

The Patterton and Darnley rifle ranges were home to three different volunteer corps. Without going into too much detail, Patterton was the rifle range and the battery for the 9th Battalion Highland Light Infantry, as it was known when it became part of the Territorial Force under the Haldane reforms of 1908. It had started life as the 105 Lanarkshire Volunteers, aka the Glasgow Highland Regiment, which was formed in 1868 by a group of Highland migrants as part of the volunteer corps. They went on to fight in World War 1 (1914-1918). They also fought in World War 11 (1939-1945) as part of the Territorial Army, which was formed in 1920.

Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment)

The Glasgow Highlanders was a former infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Territorial Force, later renamed the Territorial Army. The regiment eventually became a Volunteer Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment), which was formed in 1881. It drew its recruits mainly from Glasgow and the Scottish Lowlands. The unit took part in both the First and Second World Wars before joining with the Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1959 to become The Royal Highland Fusiliers.

A direct link between the Larne Gun Running incident in Ireland, which occurred on 24th to 25th of April 1914, and the Patterton magazine can be found in Hansard debates and newspaper articles of the time. The Larne Gun Running was an Ulster Volunteer Force operation, in response to moves towards Home Rule in Ireland, which saw in the region of, 25,000 guns and 3 million rounds of ammunition landed in Ireland, mainly at Larne in County Antrim. The arms had been purchased abroad but the movement had also been bringing arms in from Britain for a number of years preceding the incident The timing of the debate seems to indicate that there may have been a link between what was debated and the events of around 10 days later. Below are the notes from the debate:

HANSARD

158: Mr F. Hall. (Dulwich) - asked by whose instructions a circular was recently issued to the officers and men of the Highland Light Infantry, asking for the names of those who would be willing to be enrolled as special constables to defend the battalion headquarters and Patterton Magazine; what were the circumstances that made this step necessary; and whether, having regard to the conditions of their service, it was open to those concerned to have refused this duty.

159: (the UNDER-SECRETARY of STATE for WAR) Mr. Tennant – “The circular was issued by the officer commanding the 9th battalion Highland Light Infantry. This was done under a misapprehension and had no reference to any special circumstances. The answer to the last part of the question is in the affirmative.”

(Source: Highland Light Infantry (9th Battalion). HC Debs 15 April 1914 vol16)

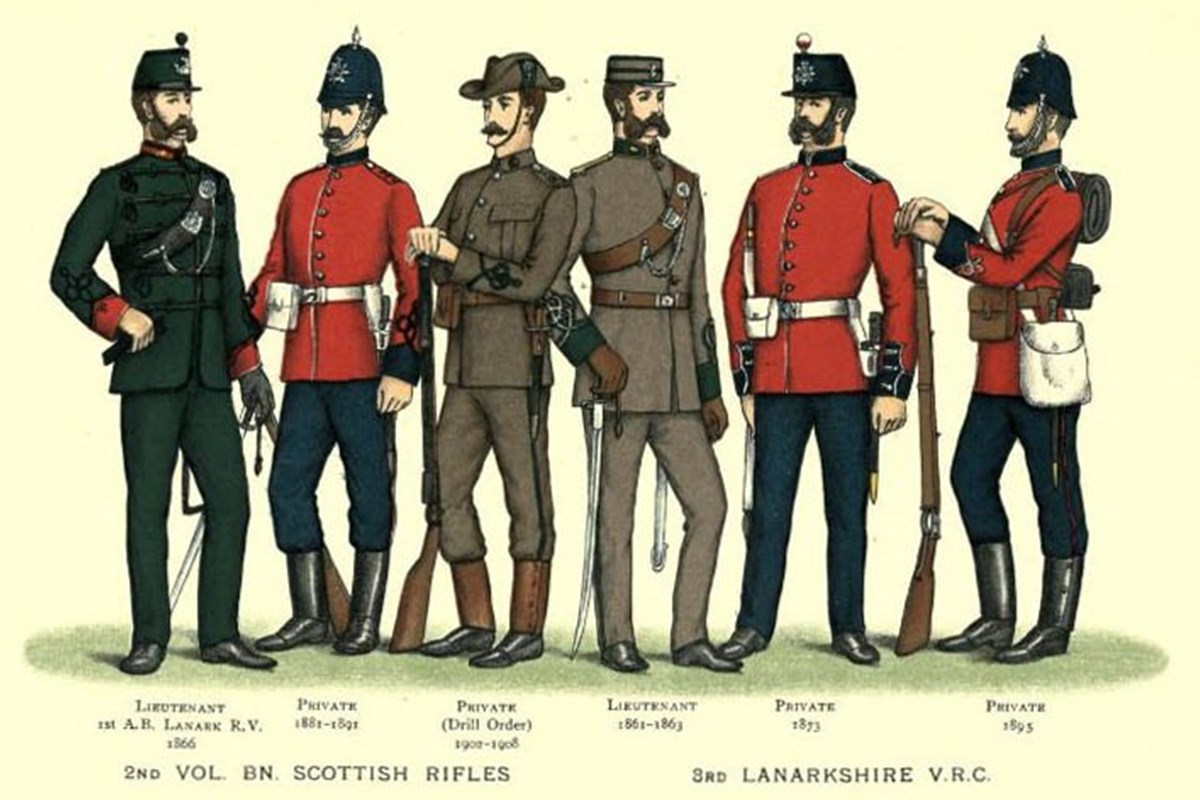

Meanwhile, the Darnley rifle ranges were used by 1st Lanarkshire Volunteers and the 3rd Lanarkshire Volunteers. Formed in 1859, the 1st Lanarkshire Volunteers became part of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1881 under army reforms. This saw some of their number fight in the Boer War (1899-1902). The regiment fought in World War I, including at the Battle of The Somme. They became the 5th Battalion Cameronians (Rifle Brigade) in the new Territorial Force under the Haldane reforms of 1908. They then became part of the Territorial Army in 1920. The regiment absorbed the 8th Cameronians the following year. The 5th/8th Cameronians became part of the Royal Artillery Searchlight Division in 1938 and served in this capacity during World War 11, including as part of the defence for the West of Scotland.

The 3rd Lanarkshire Volunteers were formed in 1859 as an amalgamation of the South Glasgow Corps. They created the famous Third Lanark Volunteer Football Club in 1872 which, amongst other achievements, went on to win the FA Cup in 1889 and 1905, and the football league in 1904. They were distinguished riflemen and two of the 3rds won the foremost prize in marksmanship, the Queen’s Prize, in the 1890s. One of them would go on to win it again a few years later.

They became part of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 1881 and went on to fight in the Boer War ( and at Gallipoli in World War 1, where they suffered huge losses. Under the Haldane reforms of 1908 they became the 7th Battalion Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), and like the 5th Battalion, they became part of the Territorial Army in 1920. During World War II they were deployed as part of the 156th Infantry Brigade to provide cover after the Normandy landings.

Anecdotal evidence cited in the Glasgow University Archaeological Research Division (GUARD) Report, Deaconsbank Structure, Project 1772, suggests that both the Patterton and Darnley ranges were used by Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACS) as a military base during WWI. The area was then expanded, as evidenced by the third edition of the 1914-1920 OS map. There is no trace of a military camp at that time. It has been speculated that this may be due to the fact it was not shown for military secrecy reasons. It has also been mooted that it may have been a tented camp. The fact that what had been the 3rd Lanarkshire Volunteers fought at Gallipoli perhaps adds weight to the theory that ANZAC troops were at the site during WWI.

The GUARD report states that the camp does not follow the standard form of The Ministry of Works design for prisoner of war camps. This suggests that there was a military camp in existence before it was used for POWs. Indeed, we have oral testimony that the camp was a military training camp at the beginning of WWII. James Rodger remembers British soldiers in a camp at Patterton in 1940 or 1941:

It was the army, the British army. Yes, it was Nissan huts all the time. What they did for heating in the wintertime I couldnae tell you. I think they just hoped for the best. The only heating they had, ah think it was a stove. A kind of stove in the hut. That was all the heating they had. But I was only in the camp, where the soldiers lived, ah was only ever in once.

I don’t have any specific recollection what they were doing at the camp. I mind o’ them going out on route marches. What was the main street in Newton Mearns? I can mind on them going out on a 15, either a 15 or a 16-mile route march. And there all marching. They were split into so many on each side o’ the road. Single file. And they walked doon the main street. And ah can…the Sergeant in charge “Give us a tune Jack.” I can min’ his words yet. An, there were one o’ the soldiers had, a, a piano accordion. He slung his rifle ontae his shooder and then he got on to the accordion, and he struck up. Now it might no’ mean anything, but he struck up Mairi’s Wedding. And I can mind it yet…it put a spring in these soldiers’ step. When he struck up with Mairi’s wedding. Ah can min’ o’ that yet. Ah do kno’. They come doon. what is noo, the [M]77. The old [A]77, they come doon it and they came in at the Cross and then went doon the main street. Ah think they were going doon the camp. Because that’s where they were headin’. They were headin’ tae Patterton camp.

James also remembers when a couple of the soldiers worked on his family’s farm, Netherplace, during the harvest:

Ma memory’s no good enough to name what regiment o’ the army it actually was. But ah can min’ o’ the two soldiers coming up here [Netherplace farm] to help wi’ the harvest. That be what? 1940, aboot ’40 or ’41. It’d be 1941. At that time, it was a’ horse and carts. A’ the harvest was brought in wi’ horse and carts. And according ti the war time regulations, we couldnae bring in the harvest and stack them in roon aboot the yard, as we did pre-war and post-war. They’d to be spread oot in case o’ fire. In case o’ bombin’ and fire. And they were a’ just stacked in the field at that time. And we had a wagon. A horse drawn wagon. And it had sides, ah would say two feet high. And, eh, the framework. The bolts stuck up about two inches. An inch and a half above the frame for more or less tae haul the sheafs when they were built. And he, one o’ the soldiers, jumped oot o’ this and caught his troosers. And ripped his army troosers fae there tae here. Right doon ti the waist. We tied ‘em up wi’ a bit o’ string. And he worked away like that a’ day (laughs) . That’s about as much as I can min’ o’ the actual harvest. But as I say, ma mother brought the two soldiers in and gave them their dinner. And if we happened to be working late, she brought them in to the hoose and they got their tea. They got their tea alang wi’ the rest o’ us. Doorsteps…oh my god. I can mine on…they were about that thickness. And I cannae…I havenae just mind whether they hid ony margarine on them or no. But ah can min’ the bread was about that thick and the bully beef wasnae much thinner [laughs]. I can always mind o’ that. But, and that’s what ma mother said, “Och, you cannae work on that.” And that’s when she brought them in for their dinner. They got their dinner alang wi’ the rest o’ us. And if we were working late, they got their tea tae.

James Rodger’s testimony provides strong evidence that there was British Army servicemen staying in the Nissan hutted Patterton Camp by 1941. He also states that, by his recollection, they stayed until 1944:

Oh, during the war. They were there tae ’43, ’44. Till the end o’ the war. The war ended in ’45. Eh, they were there. The army was there then. No sorry, the army wasnae there tae 45. They were only there tae ’44. It was then the POWs came in.

Documentary evidence confirms that 120 Coy, Pioneer Corps were based at Patterton in the summer of 1941. The Pioneer Corps regiment magazine of October 2012 contains an article called ‘What Saved Britain’, which quotes from Sgt. Murphy MP, 120 Coy, Patterton Camp, Thornliebank based there on the 17th of June 1941. He was being interviewed about an incident which happened elsewhere the year before. There is also an entry on the RootsChat.com website referring to a Pte. Cyril Vincent attached to 120 Coy at Patterton on the 25th of June 1941.

Our respondent Susan McLelland (born 1929) used to go into the camp when Italian POWs were there; she visited the camp regularly with her father when he was home on leave from the Pioneer Corps. Major William Michael Spreckley, the Patterton Camp Commandant during much of the stay of German Working Company 660, served with the Pioneer Corp, which might suggest that the Pioneer Corp were there throughout the time that POWs were at the camp. This is perhaps the reason that Susan’s father visited there:

My Dad was in the army. He was a sergeant in the Pioneer Corps. He was in the First World War as well. He was based at St Albans in England, and he used to come up fae St Albans and go up to Patterton for a walk.

The Pioneer Corps were formed in November 1940. They were a combatant and light engineering regiment. Amongst other services they took part in beach assaults in France and Italy and they built anti-aircraft sites in Britain. There may be a connection between their building of anti-aircraft sites and a footnote in the book, called Sparrow: A Chronicle of Defiance by Grant McLachlan, which refers to POWs from Patterton working at an anti-aircraft site in 1942:

The Patterton Prisoner of War Camp was established in Thornliebank in 1941. Detached work parties of prisoners were used in Clarkston in September 1942 to clear ground next to the anti-aircraft battery.