Patterton Camp’s Residential Era

The background to, and the events of, the post-WWII housing crisis are complicated. Its roots lie in the industrial revolution of the 19th century when an unprecedented amount of people moved to urban and industrial areas in pursuit of work opportunities. They were almost invariably crowded into privately rented accommodation, which often caused overcrowding, substandard living conditions and the spread of disease. Some few notable philanthropists began to build social housing from the 1850s as a response to the social problems brought about by bad housing. By the 1890s, local authorities had taken over as the main providers of this type of housing and most of it was cheaply built and high density. However, demand was high and most of the housing available to working people remained privately owned.

During WWI, a series of rent strikes were staged across Britain, with Mary Barbour famously leading the 1915 rent strikes in Glasgow. These were targeted at private landlords charging what were regarded by the protestors as unreasonable rents to people working in munitions works and other war industries. This further highlighted the problem of slum housing at a time when house building was almost at a standstill.

The day after the armistice, Prime Minister Lloyd George promised “Habitations fit for heroes who have won the war,” which was shortened in the press to ‘Homes fit for Heroes’. The reality did not live up to the promises. Slum clearance far exceeded house building during the interwar period. There were also large shortages in manpower, materials and money for house building. The 1919 Housing Act put the responsibility for house building onto the local authorities. It also put caps on the amounts of rents that could be charged, which gave the local authorities less money to build houses with.

Post-war social and political unrest and a recession in 1921 did not help matters. Throughout the 1920s, social housing provision, in terms of both quantity and quality, was subject to large regional differences. Its providers were thought to penalise those people who could not show a flawless rent book. This meant that people in uncertain jobs, such as mining and dock work were not considered for council housing. Overcrowding in existing accommodation was often caused by people taking in lodgers to help pay the rent in times of economic downturn.

Post 1926, there was an ideological rejection of public spending and therefore cuts were made to local authority housing budgets. The 1930s brought a great deal of slum clearance, with around one million people removed from these housing conditions. It has also been regarded as a time of strong government support for private building. These houses were being built for those who were reasonably financially comfortable. Only 18 per cent of manual workers were buying their houses during this period.

Housing provision between the wars was marked by the lack of consistent government subsidies towards social housing provision. It was also a time of great job uncertainty for many, which contributed to an inability for some of these people, so effected, to secure tenancies in any available social housing in their area.

During WWII, two thirds of the skilled building workforce went into the armed forces. Those that remained worked on government building contracts. 200,000 houses in Britain were destroyed by aerial bombardment, and two out of seven homes needed essential repairs. Problems of overcrowding and lack of housing provision also continued. People rented out rooms at very high rates and people would often have to leave these rooms when members of the armed forces returned home.

A post-war housing crisis had been widely anticipated, and one of the proposed solutions was the use of former army and prisoner of war facilities as temporary housing. In 1943, the post-war reconditioning of these facilities had been mooted, but not taken seriously, by the Secretary of State for Scotland, Tom Johnstone.

Clement Atlee’s post-war government prioritised the building of homes for people displaced by bombing and to address the long-standing housing deficit. This new social housing programme resulted in 79 per cent of new housing being in the hands of local authorities by 1950, with the incoming Conservative government further expanding the building of council houses. However, an initial lack of labour and materials at the end of the war led to building delays and the resulting housing shortage was particularly acute in Scotland. Local councillors made appeals for former military camps to be used to help relieve the housing problem, arguing that some units were of better quality than the proposed prefabricated buildings. The idea of using ex-army and POW camps was rejected by Nye Bevin, the Minister of Health, from 1945 to 1951, as he wanted any money available to be directed towards the building of quality housing. Some of the camps had also been earmarked as training facilities for builders and craftsmen, whilst others, including Patterton Camp, were still occupied by prisoners of war.

Despite Bevin’s opposition, people were desperate, and some had already moved into a camp in Edinburgh as early as December 1945. Robert Thomson thinks that his family moved into Patterton from the Gorbals area of Glasgow at around this time. Robert remembers there being prisoners of war in one part of the camp, which is supported by another former resident of the camp:

There was some prisoners o’ war in the camp. Because there were actually three camps. We called it top, middle and bottom. We stayed in the top camp. And there was some prisoners o’ war in the middle camp. I dunno if there was any in the bottom, but there was some in the middle camp when we moved there… We had a single end in the Gorbals. With me, my mum, my dad, big brother, big sister, a’ stayed in this single end. And when the prisoners o’ war, the Italian prisoners o’ war left the camp...I dunno how it came aboot, but we got moving intae it as a family. You got a full hut or a half hut. We got a half hut. And later on, years later…we got a full hut. And how it worked oot, I don’t know, but that’s why I ended up there. The government, I take it, moved us from the Gorbals to the camp

Robert Thomson

Members of the Polish Resettlement Corps stayed in the camp from 1947 to 1948 but we have no memories of them from our respondents who lived in the camp. Hansard records from November 1950 contain a statement from Commander Galbraith, MP for Pollok, that Patterton Camp had been occupied [by civilian families] for five years at that time.

The nationwide movement of civilians moving into former army camps and POW camps really took off in 1946. These people were called ‘squatters’ by the Department of Health, a term disliked by many former residents of these camps, including Phil Wilson:

We were certainly not 'squatters' as some reports would have you believe! Both of my parents worked full time in the potteries, and I went to the nearest local school, which was Carnwadric Primary School, when I reached school age.

Phil Wilson

Hansard records from October 1946 reveal that 143 camps across Britain were then occupied by around 6800 people. Occupation of the camps was sometimes political, led by either the Communist Party or the Independent Labour Party, whilst other occupations were grass roots affairs. For example, there were ‘kitchen conferences’, with women in Maryhill, Glasgow, making decisions about which buildings to occupy. There is also a report that young men from Maryhill and Govan climbed the barbed wire fences at Patterton to gain access to accommodation at the camp. It is unclear what date this occurred, or whether it was linked to the ‘kitchen conferences’. A lady from Maryhill points out that she had been living in one room, without heating or running water, for four years before moving into Patterton Camp. She explained that many people would have been living in far worse conditions than those they found at the camps.

Many ex-servicemen and their families moved into the camps, including a soldier from the Highland Light Infantry who brought his family to Patterton from Greenock. It is not known whether the regiment’s former links to Patterton had any bearing on his decision. Raymond Barnes’ father had been a military policeman at Patterton. They lived in a wooden hut that would have been part of the infirmary when the German POWs were there:

Well, it was the old corrugated huts. There was one hut at the beginning of the camp, which was wooden, that was the hut we stayed in because my dad was an MP, a military policeman, in the camp when it was in progress with the POWs. That was the MP’s hut, so when the prisoners were all released and taken away, the MPs obtained that hut, and my dad was one of the last MPs to be there. So, we moved in to that hut. That was the only one that was wooden, the rest was all corrugated, all tin

Raymond’s family got the hut because his father was serving at the camp, but other oral testimony and anecdotal evidence shows that people also moved into the camp of their own volitionDifferent families, more or less, people, I dunno where they all came from, different areas in Glasgow, and they all went back to different areas when the camp dispersed.

Different families, more or less, people, I dunno where they all came from, different areas in Glasgow, and they all went back to different areas when the camp dispersed.

Raymond Barnes

These men and women would have been used to similar and sometimes even more basic accommodation during the war and would have perhaps, in some cases, been inspired by their war time experiences to make risky and pragmatic decisions for the welfare of their families. The trespass laws in Scotland meant that this was a riskier decision in the early stages of camp occupation than it would have been in the rest of the UK. However, the legal issue in Scotland seems to have been mainly focused on people who were ‘squatting’ in private property. A debate on housing shortage recorded in Hansard, October 1946, shows MPs urging local authorities to go immediately into camps to make sure that water and drainage and other essential services were made available to people living in them. At this point negotiations were ongoing with local authorities about these improvements.

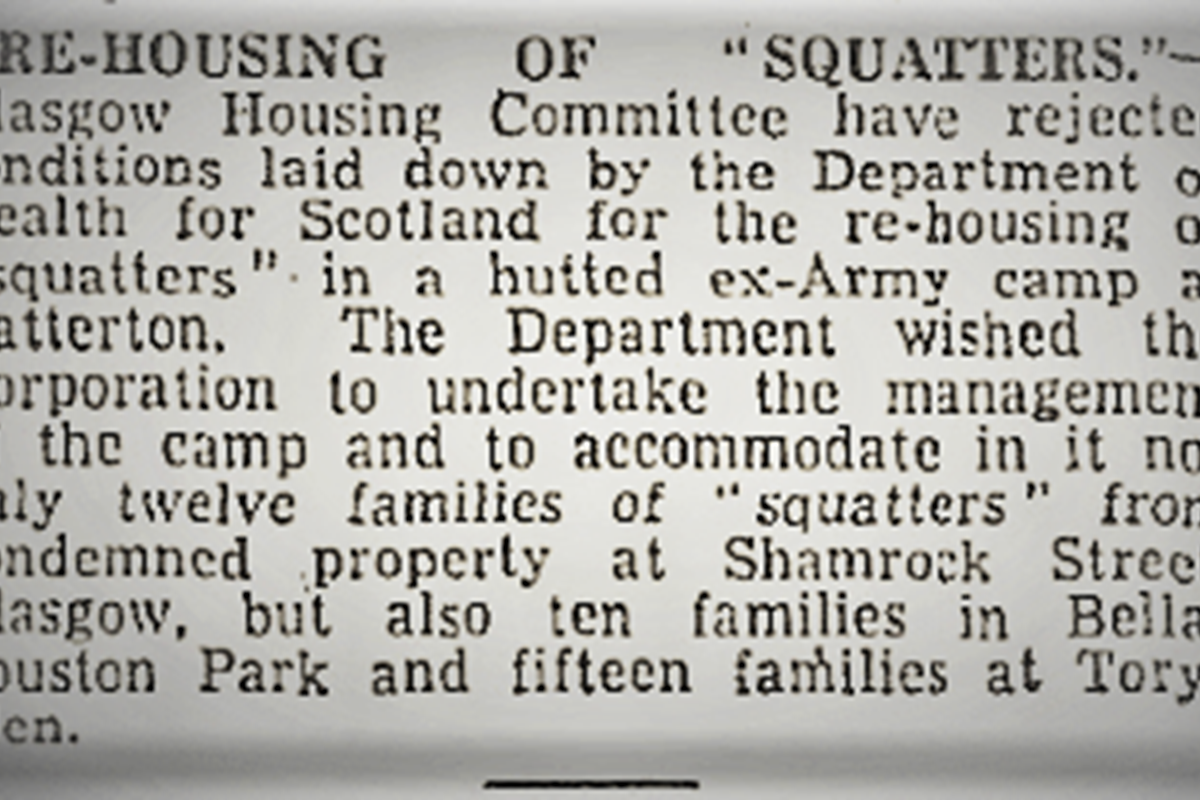

A newspaper article from the Scotsman, August 1949, states that Glasgow Housing Committee had rejected terms laid down to them by the Department of Health to undertake the management of the camp and for the re-housing of 12 families of ‘squatters’. The Glasgow Corporation did not admit ‘squatters’ onto its waiting list for council housing until 1956, almost a decade after the war had ended. It is thought that some local authorities viewed squatters as potential queue jumpers, though the people concerned claimed to have no such guile and were merely trying to put a roof above their heads. Public opinion was generally on the side of the squatters in this matter. The Department for Health for Scotland was still managing the camp in 1950 when the MP for Glasgow Pollock (which the camp came under), Commander Galbraith, discussed the camp at a Housing Scotland debate in 1950:

I have recently inspected these huts and I am perfectly amazed at the conditions which there exist. What amazed me more than anything was to be told that those who are collecting rents for these huts were reps of the Department of Health for Scotland. I discovered huts which could be made perfectly habitable under conditions existing today-not all good conditions- but which could be made very much better than they are. Many have never been divided at all, and those which have are in a most deplorable condition. There is no light in there whatsoever except by Paraffin oil. Officially there are 60 families here, unofficially perhaps more. There are four water taps for the people living in this camp and some have to proceed 60 or 70 yards to some of the taps. That should not exist, particularly if the department of health has any responsibility whatsoever. I have taken this up with the Secretary of State and he has undertaken to have a look at it. After five years we find this camp with 60 families with only four water taps. They have no other conveniences. That is a state of affairs which should not be allowed to exist, and in my opinion, it could easily be put right with small expenditure.

(Source: Commander Galbraith, Housing Scotland Debate, Hansard, 16th of November 1950)

It must be remembered that Commander Galbraith probably came from quite a privileged background, which would have informed his view of conditions at the camp. He was also obviously trying to get something done for these families in a situation in which rehousing was not necessarily going to come quickly for them. It should also be noted that it was recorded that camps run by the department of health often had the worst conditions.

Robert Thomson describes the site:

Oh, I remember very, very clearly. You came in the gates at the front. And in there you had one, two, three huts next to each other. Then you went by them and you got another three huts. And some o’ them were doubled, as in half a hut. And a full hut. And then when you went by them. You went doon a wee hill and there was a bridge specially built that looked brand new tae me. But it wisnae a’ big…It was only aboot four feet, five feet broad. An aboot ten feet long. It took you over the wee burn that was there. And it took you up the other side. There was one, two, three, four. Another four huts. You went along a kind a, flat bit. And it was a hut there on yer right. Two on yer left. And then another one straight on. And that’s the one that my uncle stayed in. Before that, there was over to yer left…there was other huts. But eventually they done away wi’ a’ them. Ah dunno why but they…maybe four o’ them five of them, just seemed tae pull ‘em doon. And that was the size o’ the camp. Wasnae a lot of people in it…eventually…Eh, I dunno, aboot ten, twelve families.

Brilliant, eh, plenty a room tae run aboot. Enjoy masel. Have fun. And there was a farm back tae back on it…We used tae go in there and steal the potatoes and the turnips.

We have evidence that there were tilly lamps in the huts. Robert Thomson remembers these and also when electricity was being introduced to the huts. It is unclear who made the improvements:

Eh, the washing…we had a big white sink… When we went in, at first, we didnae have any water...we didnae have any lights in it. We didnae have any heating tae start aff wi’. And then, I dunno whether the council or who it was…but they put lights in it, and they put water in it. Wisnae hot water. It was always cauld water. And you had to boil up any hot water you wanted.

Oral testimony suggests that there were a few more conveniences at the camp than Commander Galbraith mentioned, though it is unclear when improvements were made. Raymond Barnes remembers the large communal bath at the camp:

No - there was only one… one hut. On the far side there were three huts, in the middle one was a communal bath, a big bath in it…and that was there when we were there but nobody ever lived in that one, y’know. Because that was a communal bath and that, maybe the prisoners… when they came off playing a game of football or something like that, they just went right into, just jumped into the bath.

Phil Wilson remembers the wash house and the toilets at the camp:

The outside toilets near the entrance, which we were not allowed to go to after dark, for obvious reasons. The wash house was at the top end of the camp, where the women gathered on wash day for a bit of a natter, with all the white sinks in a line.

Robert Thomson remembers the toilets at the camp:

The toilets, oh, there was a multiple o’ toilets. ‘Coz, where we stayed there was a big hut. And in there was maybe twenty cubicles. We could just use whichever one we wanted. And that’s where yer toilets were. Never had any inside toilets. And that was the toilets that we used. So that was the ones that the prisoners o’ war used.

Our respondents also have some memories of the stoves in the huts. One talks about how these had been there since the camp’s days as an army training camp for the Pioneer Corps:

What I remember of the hut was the black range, which my mother used to take great pride in cleaning. My bed was the first on the right on entering the hut. When I was in bed, I was unable to move with all the blankets and coats piled on me! With no toilets in the huts, it was the potty under the bed, and I never wanted to get out of bed to use it, especially when I was nice and toasty under all the bed coverings.

Phil Wilson