Patterton’s Prisoners of War (POWs) Part 2

The German Presence

German Working Company 660 replaced the Italians at the camp some short time later. The Red Cross stated that 500 of the 535 prisoners had been transferred from Hanover Park Camp, Abergavenny, and all but one had been prisoners since D-Day in June 1944. There was one civilian in the camp.

In August 1945, Mr James Grant carried out a survey on the progress of the post-war re-education programme being carried out at Patterton Camp. Realising that there might well be security problems when German POWs were eventually released, the Foreign Office introduced the re-education programme just after VE day; its aim was the de-Nazification of German speaking prisoners of war.

Grant’s subsequent report of Patterton Camp mentions that the Germans were already draining and terracing the site in their spare time. This meant that they would not have had to contend for long with the soggy clay ground that the Italians found when they arrived at Patterton camp. This report also mentions that although they had little to entertain them at the camp, when compared to other camps in which they had been based, they would prefer to stay at Patterton Camp providing that the commandant was still there. The commandant, Major Spreckley, was noted to have a great practical knowledge of the re-education programme and to be able to speak some German. Born in Nottingham, Major William Michael Spreckley served with 16th Battalion Sherwood Foresters in WWI. By WWII, he was considered to be a professional, well-organised and capable officer who was well thought of by his men and, it appears, also by the German prisoners under his care. The report suggests prisoners were, in general, well-motivated and content at the camp during this period. It must be remembered that, like the Italians, many would have been traumatised by war and homesick for their own communities. Many of them would have been worried about their families living in what was now the Russian Zone of Germany. They also would not have had the freedom to wander around as the Italians had during their stay.

A slightly later International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) report, written by Frederique Bieri following an inspection on 17th November 1945, provides us with a window into the facilities available to the German prisoners. Bieri was touring Scotland’s camps and was well thought of by staff and prisoners alike. Two days before his visit to Patterton, Bieri had surveyed the much larger Pennylands Camp in East Ayrshire (read more about Pennylands at: http://cumnockhistorygroup.org/ww2-pennylands-about.html). There were 59 huts at Patterton at this stage and their various uses may shed some light on the well-being of the prisoners at the time. There was a well-stocked canteen and provisions stores. A good supply of food would have been vital to the health of the men and, under the terms of the Geneva Convention, they had to be treated well. There was a well-stocked infirmary comprised of three wooden huts, which was being made winter ready. A couple of Germans were ill at the time the report was written, one with Influenza and one with heart trouble. The health and nutrition of the prisoners was said to be generally good by the German doctor at the camp, although he thought this might be difficult to maintain given the onset of winter weather. As with the earlier Italian prisoners, access to a doctor who could speak their native language would have been an advantage to the prisoners. There was also a British dentist. There were no serious cases of disease or contagion at that time. The huts had heating and electricity and the prisoners were all issued with a sleeping bag and a blanket. There were good showers and latrines. Prisoners were all issued with large coats as some of their uniforms were in poor condition. The prisoners were authorised to go for walks, and this would have been good for both their physical and their mental health, albeit that these walks would have been supervised.

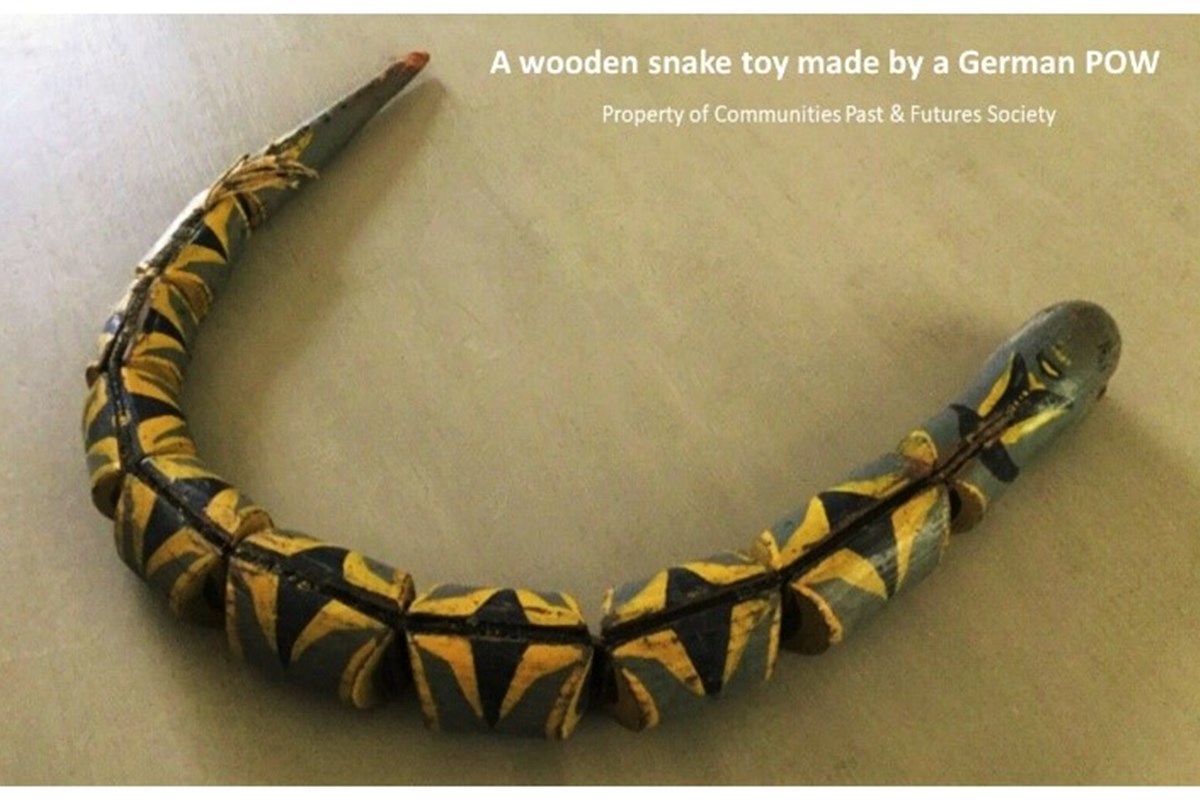

Constructive activities were deemed advantageous to the smooth running of the camp and there were carpentry, craftwork and art workshops where skilled men earned more than unskilled men. It is stated that most of the prisoners worked in these workshops, with many learning new skills that would have been useful when they returned home. During the term of the camp, prisoners often made figurines and toys, such as this wooden snake toy.

James Rodger recalls that the prisoners tried to make the camp as comfortable as possible:

They mixed the clay wi’ earth…and then they used it for whitewash. The Germans done it. But they done it with Arden lime. It was the time the Nazis were there. It was them that actually whitewashed the camp, wi’ Arden lime. Ah, they hid it looking well. They just wanted the camp to look better. I cannae just mind whether they whitewashed the, the corrugated iron, but they whitewashed a’ the ends and the sides.

There was a theatre with 12 members preparing a show for Christmas, and a choir with 30 to 35 members. There was only one musical instrument at this point, which was a violin. Whilst this does not show a great deal of participation from a camp containing 535 prisoners, it can be imagined that a good deal of the others would have been entertained by these activities. The football ground was still there and may have been used at this point. There was a film shown once a week. These activities would have provided some distraction for the prisoners.

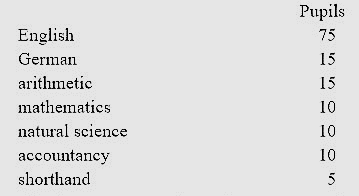

Patterton Camp also housed a library that contained some 140 books, though it lacked textbooks, which could have been demotivating for those trying to learn. A few men were taking part in educational activities (it is unclear exactly how many), and the most popular subject was English, with 75 pupils. Learning English would have been good for the men’s mental health as it would have made them feel more in control of their circumstances and less isolated in a foreign country. A Catholic priest regularly visited the camp’s chapel to deliver services.

The report mentions the sending of brown cards, which were a means for the prisoners to let their families know where they were. The commandant stated that replies had boosted the morale of the prisoners and that only a few received bad news. 160 prisoners could not send brown cards as their families were in the Russian Zone, Berlin and Czechoslovakia. Some of the men would have suffered a great deal from these circumstances. The 1945 Red Cross report concludes that the camp was generally excellent and that there were no complaints.

The report mentions the sending of brown cards, which were a means for the prisoners to let their families know where they were. The commandant stated that replies had boosted the morale of the prisoners and that only a few received bad news. 160 prisoners could not send brown cards as their families were in the Russian Zone, Berlin and Czechoslovakia. Some of the men would have suffered a great deal from these circumstances. The 1945 Red Cross report concludes that the camp was generally excellent and that there were no complaints.

The next we hear in documentary evidence of the German prisoners is in newspaper reports dating from April 1946. Two prisoners escaped from a camp near Thornliebank and after 10 days on the run they were apprehended by the police in Largs. They had been hiding in the woods on the Kelburn estate between Largs and Fairlie. One of them had been affecting an American accent and spoke fluent English. He explained that he had lived in the USA for a few years. The prisoners had a collapsible rubber dinghy in their hide out and the fluent English speaker explained to the police that his companion had rowed the boat out on the Clyde river, and that they had climbed aboard the Steamer Kind Edward under the misapprehension that it was a boat heading for Ireland. They left when they realised their mistake. It is impossible to say why these men escaped from the camp; however, it does sound like there was some planning involved and that it was not an opportunistic escape.

A follow-up re-education report stems from another visit by Mr James Grant in October 1946. The commandant is still Major Spreckley. The number of men in the camp is 600 with numbers being strengthened, temporarily, by 130 men from another working company. Grant mentions intercamp football and concert activities, suggesting that leisure activities had improved in the camp since the report of May 1945. He also notes that the men asked for a talk on a novel that they had heard about from men from another camp. This suggests that they were doing more than just playing football when visiting other camps and that there was a genuine interest in the re-education programme.

In November 1946, Paul Bondy, a lecturer on the re-education circuit, visited Patterton camp. He wrote a short note to his wife about the camp. He also wrote a report from which we have a small extract. The note is short as Bondy had little time due to having to travel to another camp the next day. He described the site as being a ‘very neat little camp’, and further mentioned that the stove in his ‘little red hut’ was very warm. He also wrote that his bed had sheets, which was not the case at Johnstone Castle Camp where he had stayed the previous evening. It is likely that the POWs also had sheets as, according to the Geneva Convention, they would have had to have been treated equally. Bundy painted a cosy picture of the mess, writing that he dined at a mahogany table in front of an open fire; he added that the ‘beautifully polished’ mahogany table had been made by the POWs. This indicates a high level of craftsmanship being carried out by some of the men in the camp. It is not clear how many prisoners attended Paul Bondy’s lecture.

The re-educational survey of March 1947 was again carried about by James Grant. The commandant is now a Major T Chapline. Grant now finds the camp with a strength of 475 prisoners, with 75 of them enrolled in the new courses. He notes that books, apart from dictionaries, were plentiful and that prisoners from the previous year were keen to sit exams and get diplomas. This shows that at least some of the prisoners were getting the benefit of education, then.

Lang posited that the intellectual level of the camp was ‘Lacking in leading personalities. Repatriation took away the best.’ He further stated that all ‘disruptive Communists and black elements’ had been taken out of the camp, meaning that Patterton had indeed housed Nazi-sympathisers or activists. By the time of this 1947 report, they had been moved to remote camps, such as Cultybraggan in Perthshire and Watten in Caithness.

Our respondent James Rodger thinks that some early prisoners at Patterton Camp were deemed to have strong Nazi ideologies and were moved to Cultybraggan camp. He thinks that these prisoners were in the camp before the Italians. Here he describes his impression of the local community’s attitude to these prisoners:

They were quite relieved to see them going. Because there was aye the possibility that they might try to escape. Because the guard patrolled the perimeter…was it every oor, two oors, or something. Ah think it was every oor. There were a guard roon aboot the whole camp… Some o’ them were in Perthshire. I think the camp’s still there yet. Aye, some were up in Perthshire…because they were liable to escape. Liable to try to escape.

We have evidence from a historical biography that there were POWS staying at Patterton camp in 1942. In the book, Sparrow: A Chronicle of Defiance, by Grant McLauchlan, the following footnote appears:

The Patterton Prisoner of War Camp was established in Thornliebank in 1941. Detached work parties of prisoners were used in Clarkston in September 1942 to clear ground next to the anti-aircraft battery.'

As noted earlier, both documentary evidence and personal testimony describe that a military camp of some form was in existence at Patterton in 1941, so it is possible there were POWs there in 1942. Whether they would have been German or Italian is unclear.

Additional testimonies offer an insight into the local population’s interactions with the German prisoners, though most of these memories are difficult to date. Alan Flower remembers himself and his young friends having good natured snowball fights with the prisoners. He also confirms that some of the Germans at one point worked at the printworks in Thornliebank:

The other thing I remember, and these definitely were Germans, they used to march them from the camp down to the printworks in Thornliebank, to do a daily duty. They went down in the morning and they came back in the evening. Now, this was during winter, when there was a lot of snow on the ground. And, my friends and I used to hide behind a hedge at the junction of Arden Avenue with Stewarton Road. And when the prisoners were going past…in fact, the hedge was the boundary of what, something Lane running and cricket ground as was then. It’s now the David Lloyd’s fitness centre. We used to hide behind there and as they [the prisoners] went past, we pelted them with snowballs. Now, it was all done in good spirit, there was no animosity or anything. But they obviously….the Germans were getting wise to this…and on the way back, this particular day, they were all marching. And they had the big yellow capes which draped over everything and they were marching past. And we all stood up to throw our snowballs. They brought out these massive great, things, from underneath their coats or capes and hurled them into the hedges. And we were all covered in snow.

This is a poignant piece of testimony as it can be imagined that the Germans would have missed the company of children from their families and probably enjoyed these interactions as a result.

Andrew Brown (born 1937) remembers Germans working on Greenlaw Farm, where his family lived, and said this about some of their activities:

The German prisoners that we had were quite good. They used to make things out of bits o’ wood and then go doon the village and sell them, to get a few bob. I also remember them…they used to steal potatoes and they made, hooch, hooch, hooch, aye! They had this wee stil. They made a wee stil. Made this stuff and took it doon the village and sold it, until we found out they were doing it. My father found oot anyway. He had to phone the camp and tell them to come and take them [the prisoners] away. Because they were stealing tatties, they were stealing eggs. And things like that were beginning to disappear…

Alistair Mutrie moved to Carnwadric at the age of 10 and vividly recalls chatter about the then long-gone POW camp:

The women used to talk, you know, and you would hear them talking about [the prisoners] getting marched down from the camp. Right down into Thornliebank. Now whether they entered the main gate, I’m not sure about that… They [the prisoners] used to hand toys to the kids. So, I imagine there was a gate and somewhere along Carnwadric Road. That’s away at the other side… Just wood toys, card...but, there was a good...I mean, I never heard one person, no, women or men, say anything bad about these prisoners. There was almost an affection, because of these hand-outs to the children, you know. There was no catcalling or animosity or anything like that. I never gathered that. I always got that impression, listening to the older people.

We have testimony from James Rodger that a German POW named Paul remained in Scotland and worked at Langton Farm into the 1950s:

Paul was at Langton till ’53, ’54. Aye, he was there for a good while after the war. Because, he used to get Bobby Turner tae gi’ him the Scottish Farmer. And he had enough English that he could read bits o’ it. But he was an awfy nice chap, Paul. His home was in East Germany. And he didn’t…He’d been back [there] on a visit. And it was somewhere in East Germany. Well, as you’ll probably know, by that time East Germany was under the Russians. Paul went back to what was the Berlin Wall. And some of the ones he was brought up wi’, he was speaking to them through the wall. And after that, “No, no, no, I’ll no go back, I’ll no go back,” he said. “I would go back if East Germany was free, if we could do what we liked. Walk aboot as we liked, I would go back.” He did eventually go back, after. I cannae mind when the Berlin Wall was taken doon. But he went back after. East Germany was free o’ Communism.

There were another German POW on Faulds Farm. And when they met up, we didnae ken a word of whit they were sayin’. They were yattering away in German. It’s diversifying away a bit from the camp, but I always mind on Paul. I dunno what his second name was. He really was an awfa nice man. An awfa nice chap. As I say he was…but he had broken English by this point, and he was quite keen tae to talk to you. Admittedly, if he could understand me, I don’t know.